The outcry over the rise of fake news belies the arguably greater hazard long afflicting the scientific community: fake science.

Since 2005, when Stanford University’s John Ioannidis published his explosive essay “Why Most Published Research Findings Are False” science has been on the defensive.

It’s not too hard to see how we got here. Fake research is considerably easier and more affordable than the real thing. We no longer have the luxury of a lucrative missile gap that turned pocket protectors into a popular fashion accessory for a generation of engineers, physicists and computer scientists. (Curiously, recent declassified documents now reveal the missile gap about alleged Russian nuclear superiority, as parodied in movies like Dr. Strangelove, to be entirely false.)

Much to the dismay of leading universities, public funding for scientific research has been drying up since the end of the Cold War with the U.S. dropping from second to 12th in a ranking of developed countries. The trend seems unlikely to reverse in a Trump administration deeply skeptical of even climate warming. These are hard times for science.

It’s the billionaires, not government, with deep pockets now, as the likes of Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos gaze up to the heavens and compete with each other for lucrative NASA contracts that all but keep their “private” ventures afloat. At least they’re having fun and trying to restore space travel’s long lost luster.

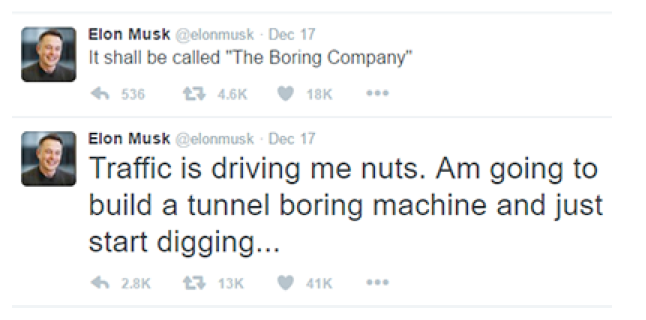

Of all his peers, Musk may be most at risk of having his words morph into fake news if he’s not jokingly doing so already. On Twitter, his recent “announcement” of underground tunnels as a traffic solution sparked headlines.

Possibly oblivious to the wordplay on archrival The Boeing Company as “The Boring Company” Musk watchers started believing him, prompting Musk to play along with another tweet claiming “I am actually going to do this.” And according to Musk biographer Ashlee Vance, his earlier support of Hyperloop vacuum tubes began more as a way to belittle California’s proposed high speed rail, as the world’s slowest bullet train, than a serious endeavor intended to be go beyond mere theoretical musing.

Described by Musk as “across between a Concorde, a railgun and an air hockey table” Hyperloop quickly won many admirers on social media and even interest from President Obama and former Nevada senator Harry Reid.

But reaction from a few so-called transit experts remained equally sobering, lampooning the idea as a “terrifying ‘barf ride’ that would subject riders to violent g-forces and uncomfortable rolling, accelerating, and braking.” For now, Musk’s mojo could be enough to keep the idea alive if only as an “open source” project with its own Wikipedia page and a trademarked name.

Talking about mojo, only time will tell if Musk defies skeptics and one day reaches Mars. His biggest challenge getting there could come down to a war on fake science itself — extracting the hype out of every conceivable variable from unbreakable O rings to unbendable “space-grade” glass.

As Vance described in his biography, Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic Future, “space-grade” custom-made parts can typically be replaced by off-the-shelf components at much lower cost. Along with original research into rocket design, Musk’s efforts helped slash the cost of space launches, upending the dominance of NASA contractors like Boeing and Lockheed.

Maybe now “space-grade” is more fiction than unassailable fact.