Carbon nanotubes are present in a lot of places around us. They’re a part of the manufacturing of golf clubs, car parts, solar cells, batteries, textiles and even human tissue engineering. It’s generated in labs by material researchers, and recently, it’s been revealed that plentiful amounts of it could be found in vehicle exhaust.

This week, however, it was found in a much less likely place: the lungs of 64 Parisian children.

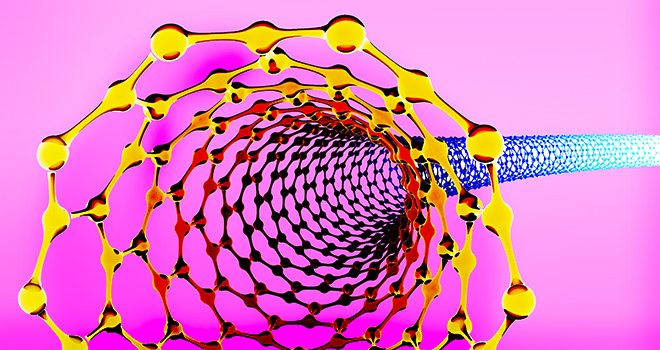

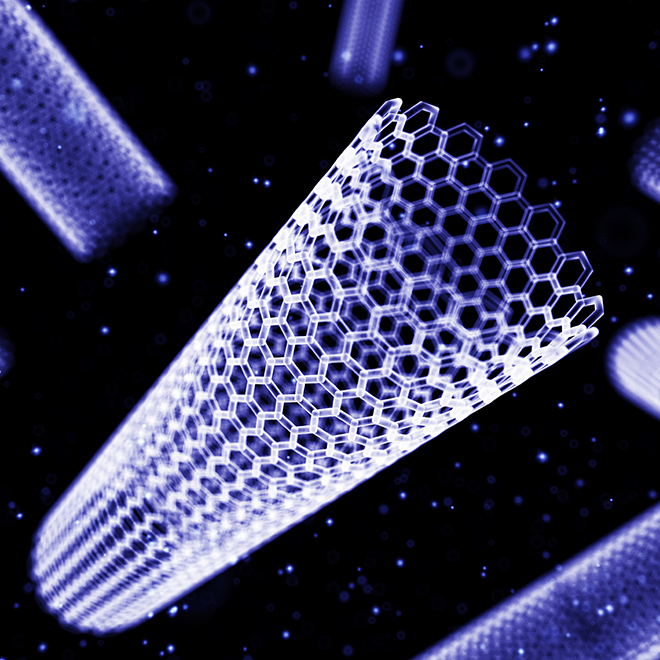

Carbon nanotubes are a sort of miracle material. It’s strong, very elastic and make for good conductors of temperature and electricity.

A team of scientists from Rice University in Texas working with fellow researchers in France discovered carbon nanotubes in liquid from the airways of the French children during customary asthma treatment; the same kind of carbon nanotubes found in exhaust pipes in Parisian cars and in smog from around the city.

The complete report can be found in a paper published in EBioMedicine. According to Lon Wilson, chemist from the Rice University team and co-author of the paper, the way that scientists create nanotubes in labs is somewhat similar to the process of turning a car’s toxic carbon monoxide emissions into safer exhaust, through a catalytic converter. The chemist added that it’s likely that everyone in the world as some carbon nanotubes in their lungs from breathing air laced with car exhaust. It’s slightly ironic that everyone walking around may be breathing the air they mask themselves to avoid in their labs.

They Were Never Found in Humans Before

This is the first time nanotubes have been detected in humans. The investigation, carried out by Fathi Moussa and colleagues at the University of Paris-Saclay, took samples from the 64 children, and carbon nanotubes were found in every single sample. Five of them even had them in their lung’s macrophages, which are immune cells that clear unwanted particles from the airways.

More Studies Should Be Made to Find Any Adverse Effects

Asthmatic people have weakened macrophages, which makes them more sensitive to particles in the air, and the fact that these nanotubes have latched onto those cells makes it even more difficult to filter good particles from bad ones. However, the amount found is not enough to be conclusive.

Though the nanotubes aren’t directly toxic, they are large in terms of surface, and they’re sticky, making it much easier for pollutants to get deep into the long and even cross membranes, as Moussa adds, but further research is needed to see how damaging these carbon nanotubes are, and in what concentrations they linger in people’s lungs as well as any relation to respiratory diseases or malfunctions. Carbon nanotubes have similar components to asbestos, and could be very harmful if these findings are not followed up.